-

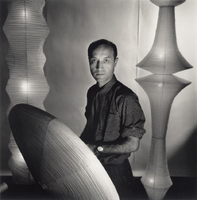

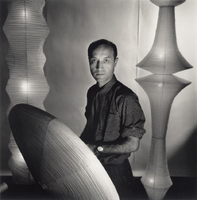

Noguchi, Isamu, 1904-1988

Noguchi, Isamu, 1904-1988

-

Hepworth, Barbara, 1903-1975

Hepworth, Barbara, 1903-1975

-

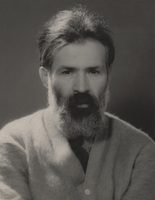

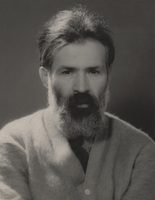

Arp, Jean, 1887-1966

Arp, Jean, 1887-1966

-

Brancusi, Constantin, 1876-1957

Brancusi, Constantin, 1876-1957

-

The Miracle (Seal [I])

The Miracle (Seal [I]) Constantin Brancusi revisited subjects and forms frequently throughout his career, executing variations of earlier sculptures with subtly reimagined contours and in new mediums and scales. Both The Miracle (Seal [I]) (Le miracle, ca. 1930–32) and Flying Turtle (Tortue volante, 1940–45) were the first of their kind and relatively late additions to the artist’s repertoire of motifs; in fact, Flying Turtle was the last sculpture Brancusi executed that did not have a direct formal precedent. The two works do, however, show a continuity with many of the sculptor’s overarching concerns.

Animals were a common subject for Brancusi, though excepting humans, he focused exclusively on those that fly or swim. The shapes of such animals were suited to the compact volumes that the sculptor favored, as well as his desire to depict speed and movement. In The Miracle (Seal [I]) and Flying Turtle, the simplified forms suggest not only the creatures’ namesakes but also their fluid means of locomotion. By balancing both sculptures delicately on their respective limestone bases and giving each a pronounced upward thrust, Brancusi captured the seeming weightlessness of bodies suspended in water or air. The effect is striking given the significant mass of these two marble works.

For Brancusi, animals also held symbolic weight and transcendent possibilities. In the case of The Miracle (Seal [I]), the breaching form may allude to emotional regeneration, as inspired by the sight of an acquaintance of the artist experiencing catharsis while swimming. Such transformational potential is taken a step further in Flying Turtle. By imaginatively endowing the subject with flight, Brancusi created an emblem of the lowliest creature’s ability to transcend its station.

-

Brilliance

Brilliance

-

Gregory

Gregory Gregory is inspired by Gregor, the main character in Franz Kafka’s absurdist novella, The Metamorphosis. After waking one morning to find he has become a large insect, Gregor’s life slowly deteriorates as the last remnants of his human life are lost and his family turns on him, burdened by the responsibility of caring for the house’s former breadwinner while hiding him from outsiders. Gregor, though at first casually inconvenienced by his fate, cannot live with the discomfort he has brought to his family and ultimately dies to avoid furthering burdening them further.

-

Cronos

Cronos

-

Two Figures (Menhirs)

Two Figures (Menhirs) The title conflates Hepworth's recurrent theme of two figures in harmonious conjunction with her interest in the ancient standing stones that can be seen in the landscape around St Ives. Appropriately, this work is carved from Cornish slate. The artist's first slate sculptures were carved from the bed of an old billiards table. The larger figure contains a striking fossil, which was created by a small creature swimming through the silt that solidified, preserving the pattern of eddying mud in the stone.

-

Pelagos

Pelagos Pelagos (‘sea’ in Greek) was inspired by a view of the bay at St Ives in Cornwall, where two stretches of land surround the sea on either side. The hollowed-out sculpture has a spiral form resembling a shell, a wave or the roll of a hill. Hepworth wanted the taut strings to express ‘the tension I felt between myself and the sea, the wind or the hills’. She moved to Cornwall with her husband, painter Ben Nicholson in 1939 and produced some of her best-known sculpture inspired by its wild landscape.

-

Oval Sculpture No. 2

Oval Sculpture No. 2

-

Growth (Croissance)

Growth (Croissance)

-

Human Concretion

Human Concretion

-

Sculpture To Be Lost in the Forest

(Sculpture à être perdue dans la forêt)

Sculpture To Be Lost in the Forest

(Sculpture à être perdue dans la forêt) In the 1920s and 1930s Arp developed a type of biomorphic sculpture that suggested a parallel between artistic creativity and creation in nature. The shapes in his work evoke worn pebbles, buds and other natural forms. He created these sculptures using a quasi-automatic process of sanding away at a plaster model until he was satisfied with the shape. ‘I work until enough of my life has flowed into its body’, he said. His efforts to link his work with nature included placing sculptures in the forest near his home at Meudon, where they could be discovered by unsuspecting passers-by.

-

Brancusi, Constantin, 1876-1957. Endless column

Brancusi, Constantin, 1876-1957. Endless column This sculpture is the earliest extant Endless Column. In preceding years Brancusi had used a single or double pyramid as a base for his sculpture, but he eventually came to see this abstract construction as a fully realized work in its own right. Carved from oak, this succession of pyramids forms a rhythmic and undulating geometry that suggests the possibility of infinite expansion. Like other favorite motifs, this was one that Brancusi would return to over the course of his career. In the mid-1920s, he carved an Endless Column for his friend the photographer Edward Steichen that rose more than twenty-three feet. And in 1937 Brancusi erected a steel Endless Column in Tîrgu-Jiu, Romania, that soared more than ninety-eight feet into the air. That Endless Column, his last, was part of a larger sculptural ensemble that included The Gate of the Kiss and Table of Silence, which formed the artist’s only foray into public sculpture.

-

Mlle Pogany

Mlle Pogany This sculpture is a portrait of Margit Pogany, a Hungarian artist who sat for Brancusi several times in 1910 and 1911 while she was in Paris studying painting. Shortly after her return to Hungary, Brancusi carved a marble Mlle Pogany from memory, then made a plaster mold of the work, from which he cast four additional versions, including this one, in bronze. In representing its subject through highly stylized and simplified forms, the work was a significant departure from conventional portraiture. Large almond-shaped eyes overwhelm the oval face, and a black patina represents the hair that covers the top of the head and extends over the elaborate chignon at the nape of the neck. As with other motifs, this was a subject Brancusi would return to and rework in the years to come.

Noguchi, Isamu, 1904-1988

Noguchi, Isamu, 1904-1988

Hepworth, Barbara, 1903-1975

Hepworth, Barbara, 1903-1975

Arp, Jean, 1887-1966

Arp, Jean, 1887-1966

Brancusi, Constantin, 1876-1957

Brancusi, Constantin, 1876-1957

The Miracle (Seal [I]) Constantin Brancusi revisited subjects and forms frequently throughout his career, executing variations of earlier sculptures with subtly reimagined contours and in new mediums and scales. Both The Miracle (Seal [I]) (Le miracle, ca. 1930–32) and Flying Turtle (Tortue volante, 1940–45) were the first of their kind and relatively late additions to the artist’s repertoire of motifs; in fact, Flying Turtle was the last sculpture Brancusi executed that did not have a direct formal precedent. The two works do, however, show a continuity with many of the sculptor’s overarching concerns. Animals were a common subject for Brancusi, though excepting humans, he focused exclusively on those that fly or swim. The shapes of such animals were suited to the compact volumes that the sculptor favored, as well as his desire to depict speed and movement. In The Miracle (Seal [I]) and Flying Turtle, the simplified forms suggest not only the creatures’ namesakes but also their fluid means of locomotion. By balancing both sculptures delicately on their respective limestone bases and giving each a pronounced upward thrust, Brancusi captured the seeming weightlessness of bodies suspended in water or air. The effect is striking given the significant mass of these two marble works. For Brancusi, animals also held symbolic weight and transcendent possibilities. In the case of The Miracle (Seal [I]), the breaching form may allude to emotional regeneration, as inspired by the sight of an acquaintance of the artist experiencing catharsis while swimming. Such transformational potential is taken a step further in Flying Turtle. By imaginatively endowing the subject with flight, Brancusi created an emblem of the lowliest creature’s ability to transcend its station.

The Miracle (Seal [I]) Constantin Brancusi revisited subjects and forms frequently throughout his career, executing variations of earlier sculptures with subtly reimagined contours and in new mediums and scales. Both The Miracle (Seal [I]) (Le miracle, ca. 1930–32) and Flying Turtle (Tortue volante, 1940–45) were the first of their kind and relatively late additions to the artist’s repertoire of motifs; in fact, Flying Turtle was the last sculpture Brancusi executed that did not have a direct formal precedent. The two works do, however, show a continuity with many of the sculptor’s overarching concerns. Animals were a common subject for Brancusi, though excepting humans, he focused exclusively on those that fly or swim. The shapes of such animals were suited to the compact volumes that the sculptor favored, as well as his desire to depict speed and movement. In The Miracle (Seal [I]) and Flying Turtle, the simplified forms suggest not only the creatures’ namesakes but also their fluid means of locomotion. By balancing both sculptures delicately on their respective limestone bases and giving each a pronounced upward thrust, Brancusi captured the seeming weightlessness of bodies suspended in water or air. The effect is striking given the significant mass of these two marble works. For Brancusi, animals also held symbolic weight and transcendent possibilities. In the case of The Miracle (Seal [I]), the breaching form may allude to emotional regeneration, as inspired by the sight of an acquaintance of the artist experiencing catharsis while swimming. Such transformational potential is taken a step further in Flying Turtle. By imaginatively endowing the subject with flight, Brancusi created an emblem of the lowliest creature’s ability to transcend its station. Brilliance

Brilliance

Gregory Gregory is inspired by Gregor, the main character in Franz Kafka’s absurdist novella, The Metamorphosis. After waking one morning to find he has become a large insect, Gregor’s life slowly deteriorates as the last remnants of his human life are lost and his family turns on him, burdened by the responsibility of caring for the house’s former breadwinner while hiding him from outsiders. Gregor, though at first casually inconvenienced by his fate, cannot live with the discomfort he has brought to his family and ultimately dies to avoid furthering burdening them further.

Gregory Gregory is inspired by Gregor, the main character in Franz Kafka’s absurdist novella, The Metamorphosis. After waking one morning to find he has become a large insect, Gregor’s life slowly deteriorates as the last remnants of his human life are lost and his family turns on him, burdened by the responsibility of caring for the house’s former breadwinner while hiding him from outsiders. Gregor, though at first casually inconvenienced by his fate, cannot live with the discomfort he has brought to his family and ultimately dies to avoid furthering burdening them further. Cronos

Cronos

Two Figures (Menhirs) The title conflates Hepworth's recurrent theme of two figures in harmonious conjunction with her interest in the ancient standing stones that can be seen in the landscape around St Ives. Appropriately, this work is carved from Cornish slate. The artist's first slate sculptures were carved from the bed of an old billiards table. The larger figure contains a striking fossil, which was created by a small creature swimming through the silt that solidified, preserving the pattern of eddying mud in the stone.

Two Figures (Menhirs) The title conflates Hepworth's recurrent theme of two figures in harmonious conjunction with her interest in the ancient standing stones that can be seen in the landscape around St Ives. Appropriately, this work is carved from Cornish slate. The artist's first slate sculptures were carved from the bed of an old billiards table. The larger figure contains a striking fossil, which was created by a small creature swimming through the silt that solidified, preserving the pattern of eddying mud in the stone. Pelagos Pelagos (‘sea’ in Greek) was inspired by a view of the bay at St Ives in Cornwall, where two stretches of land surround the sea on either side. The hollowed-out sculpture has a spiral form resembling a shell, a wave or the roll of a hill. Hepworth wanted the taut strings to express ‘the tension I felt between myself and the sea, the wind or the hills’. She moved to Cornwall with her husband, painter Ben Nicholson in 1939 and produced some of her best-known sculpture inspired by its wild landscape.

Pelagos Pelagos (‘sea’ in Greek) was inspired by a view of the bay at St Ives in Cornwall, where two stretches of land surround the sea on either side. The hollowed-out sculpture has a spiral form resembling a shell, a wave or the roll of a hill. Hepworth wanted the taut strings to express ‘the tension I felt between myself and the sea, the wind or the hills’. She moved to Cornwall with her husband, painter Ben Nicholson in 1939 and produced some of her best-known sculpture inspired by its wild landscape. Oval Sculpture No. 2

Oval Sculpture No. 2

Growth (Croissance)

Growth (Croissance)

Human Concretion

Human Concretion

Sculpture To Be Lost in the Forest

(Sculpture à être perdue dans la forêt) In the 1920s and 1930s Arp developed a type of biomorphic sculpture that suggested a parallel between artistic creativity and creation in nature. The shapes in his work evoke worn pebbles, buds and other natural forms. He created these sculptures using a quasi-automatic process of sanding away at a plaster model until he was satisfied with the shape. ‘I work until enough of my life has flowed into its body’, he said. His efforts to link his work with nature included placing sculptures in the forest near his home at Meudon, where they could be discovered by unsuspecting passers-by.

Sculpture To Be Lost in the Forest

(Sculpture à être perdue dans la forêt) In the 1920s and 1930s Arp developed a type of biomorphic sculpture that suggested a parallel between artistic creativity and creation in nature. The shapes in his work evoke worn pebbles, buds and other natural forms. He created these sculptures using a quasi-automatic process of sanding away at a plaster model until he was satisfied with the shape. ‘I work until enough of my life has flowed into its body’, he said. His efforts to link his work with nature included placing sculptures in the forest near his home at Meudon, where they could be discovered by unsuspecting passers-by. Brancusi, Constantin, 1876-1957. Endless column This sculpture is the earliest extant Endless Column. In preceding years Brancusi had used a single or double pyramid as a base for his sculpture, but he eventually came to see this abstract construction as a fully realized work in its own right. Carved from oak, this succession of pyramids forms a rhythmic and undulating geometry that suggests the possibility of infinite expansion. Like other favorite motifs, this was one that Brancusi would return to over the course of his career. In the mid-1920s, he carved an Endless Column for his friend the photographer Edward Steichen that rose more than twenty-three feet. And in 1937 Brancusi erected a steel Endless Column in Tîrgu-Jiu, Romania, that soared more than ninety-eight feet into the air. That Endless Column, his last, was part of a larger sculptural ensemble that included The Gate of the Kiss and Table of Silence, which formed the artist’s only foray into public sculpture.

Brancusi, Constantin, 1876-1957. Endless column This sculpture is the earliest extant Endless Column. In preceding years Brancusi had used a single or double pyramid as a base for his sculpture, but he eventually came to see this abstract construction as a fully realized work in its own right. Carved from oak, this succession of pyramids forms a rhythmic and undulating geometry that suggests the possibility of infinite expansion. Like other favorite motifs, this was one that Brancusi would return to over the course of his career. In the mid-1920s, he carved an Endless Column for his friend the photographer Edward Steichen that rose more than twenty-three feet. And in 1937 Brancusi erected a steel Endless Column in Tîrgu-Jiu, Romania, that soared more than ninety-eight feet into the air. That Endless Column, his last, was part of a larger sculptural ensemble that included The Gate of the Kiss and Table of Silence, which formed the artist’s only foray into public sculpture. Mlle Pogany This sculpture is a portrait of Margit Pogany, a Hungarian artist who sat for Brancusi several times in 1910 and 1911 while she was in Paris studying painting. Shortly after her return to Hungary, Brancusi carved a marble Mlle Pogany from memory, then made a plaster mold of the work, from which he cast four additional versions, including this one, in bronze. In representing its subject through highly stylized and simplified forms, the work was a significant departure from conventional portraiture. Large almond-shaped eyes overwhelm the oval face, and a black patina represents the hair that covers the top of the head and extends over the elaborate chignon at the nape of the neck. As with other motifs, this was a subject Brancusi would return to and rework in the years to come.

Mlle Pogany This sculpture is a portrait of Margit Pogany, a Hungarian artist who sat for Brancusi several times in 1910 and 1911 while she was in Paris studying painting. Shortly after her return to Hungary, Brancusi carved a marble Mlle Pogany from memory, then made a plaster mold of the work, from which he cast four additional versions, including this one, in bronze. In representing its subject through highly stylized and simplified forms, the work was a significant departure from conventional portraiture. Large almond-shaped eyes overwhelm the oval face, and a black patina represents the hair that covers the top of the head and extends over the elaborate chignon at the nape of the neck. As with other motifs, this was a subject Brancusi would return to and rework in the years to come.