“All art is erotic”

-Gustav Klimt

It is certainly a different time in 2020 than it was at the start of the Vienna Secession in 1897. Gustav Klimt, one of the founders of the movement, is only one of the many male artists whose work has not aged well in the eyes of feminism. His work is coveted, worth millions of dollars, the focus of supreme court cases and the highlight of museums around the world. The question is, how has a man who was known to work in his studio in the nude amongst his nude models, many of whom gave birth to his illegitimate children, and drew onanism for no other reason than for his own pleasure; be mistaken for a sexual liberator of women and feminist?

Through 10 of his artworks, it is clear that Klimt painted and drew woman as anything but ornament to his own work. He focuses on the curves and lines of women’s bodies just as he focuses on the reflection and ornamentation of his gold leaf. In his sketches, he draws women without hands or feet, the thickest and most drawn over lines are that of the lines surrounding women’s genitals. In his paintings, the figures often have the same face, and the subject of the painting is often a sexualized rendition of myth, or simply an allegory for what Klimt believes a woman’s function is.

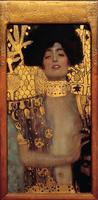

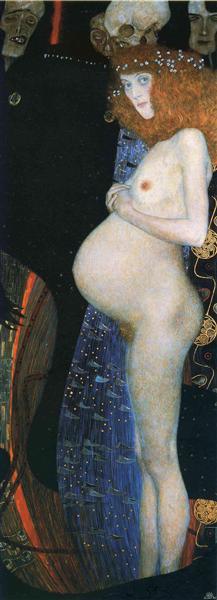

On the first page of this site, you will find 6 paintings and 2 drawings from Klimt’s golden phase. The Virgin (1913), Three Ages of Woman (1905), Danae (1907-1908), Judith with the Head of Holofernes (1901), Hope I (1903), Water Snakes II (1907), Jurisprudence (1903), Standing Nude (1906-1907), and Reclining Nude with Outstretched Left Arm (1903-1904). Each of these artworks highlights the ways in which Klimt used women as ornament or depicted them as he saw them: for sex and for reproduction. For example, Judith with the Head of Holofernes (1901) is a painting depicting the myth of Judith who slays Holofernes. In the myth, Judith bravely decapitates Holofernes, who has come with his army to destroy Judith’s city. In Klimt’s version Judith is pictured bare-breasted, with her mouth slightly open, the head of Holofernes cut off by the edge of the page. Nothing about this tells the story except for the severed head, and instead Judith is highly sexualized.

Another example is Danae (1907-1908) who is another mythical figure. In her story, her father is told a prophecy that he will be killed by his grandson, so he locks Danae in a tower so she can never have a child. Zeus, or course, finds her beautiful and impregnates her through a golden shower. In Klimt’s painting of her, Danae is in the fetal position, nude, and with a cloud of gold coins between her legs. This is the moment Klimt is painting her in: the moment that Zeus is impregnating her. She is curled up on her back, her head is touching her knees, one hand is disappearing behind her leg, possibly between her legs, and the other hand is clutching her breast. Her head is turned towards us with closed eyes, and she is blushing.

The painting is highly reminiscent of embryonic development. Danae is in the fetal position, she is surrounded by a bubble, which is like a womb. Danae, is therefore, not only a painting of what is essentially a rape, but it is a painting that is objectifying the female body by classifying it by its function: for men’s sexual pleasure and procreation.

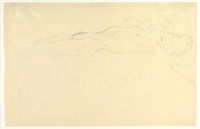

For the Last Example of his golden works there is Reclining Nude with Outstretched Left Arm (1903-1904). The sketch is odd, lightly drawn only in the top third of the page; a woman laying down from the knees up. Her only visible arm is cut off at the wrist as it goes off the right side of the page and her only surroundings are what appears to be material on the other side of her head going into the picture plane and behind her breasts. The woman is ridiculously skinny, starving looking. Her ribs are showing, her stomach is caving in and her back creates an unnatural arch as if it has no muscle to support her organs. Her hip bones protrude upwards towards the top of the painting and her hip is visible as if she is just a skeleton with a thin layer of skin. Just from her lower half it should be assumed that her face would retain the same starved and gauntness the rest of her body articulates, but it is a full beautiful face. Her breasts are two ovals sitting on top of a skeleton, her nipples perfect circles. Her face is full, her eyes closed as if peacefully asleep and unaware of the rest of her body’s trauma, and her outstretched arm looks, if anything, not proportionate to any part of her body.

Not only is this drawn in a way that accentuates the parts of her body that Klimt is more focused on, but her body is cut out of all those important pieces he didn’t include. Cutting her off at the knees and not including any hands gives the figure a look of helplessness. By removing her arms and feet the woman is basically a head attached to her genitalia, even more emphasized by her protruding ribs and sunken stomach. Klimt chose to draw her not only nude and laying down, which is an extremely vulnerable position, but he also chose to draw her unfinished, caught in a moment of stretching out an arm and stuck in the action of waking. He gives no hint of where the figure might be, there is nothing underneath her or above her, she is simply floating in space. The only thing visible is the bundle of material beside her head which somehow extenuates how thin and starved her lower half is and makes the shape of the drawing and figure much more confusing.

The lines in the sketch are faint in unimportant areas like where her legs disappear into the paper beneath her knees or her wrist going off the page. In areas of more importance the lines are darker, like on her stomach. The lines are dark and reinforced as if Klimt went back over the area several times to emphasize the hollowness of her stomach and back. The lines of the material next to her and of her hair are wavy, to apply a slight texture or movement to them. The lines seem hurried as if Klimt was trying to capture them in a single moment as the figure stretches out her arm. His lines are far from the arabesques of his artist counterparts, instead the lines are curved in areas like her face and breasts, but jagged and edged in places like her ribs and hips. It’s almost as if the viewers eye is meant to glide along the smooth lines and get caught on the harshness of the edges.

The most striking and horrific part of this drawing is how thin and starved the figure looks. Focusing on the female form in modernism is typical, but there is an almost brutality to the starvation of this figure. It must be nearly impossible to be alive and be as thin as this woman is, if she were to stand up, or even sit, she looks as if she could snap in half. Her entire rib cage is showing, her entire hip bone is sticking out in angles, there is absolutely no fat or muscle in this woman. If the male gaze is a notion towards the objectification and sexualization of women, then is this something that the male gaze has created? She is a woman in a vulnerable position, she is asleep, she is exposed, she is reclining, but is she not also concerning to look at?

The sketch creates a balance in the figure between the sexualization and violence in it. She is highly erotic, but she is also unlike other female nudes. There are faint lines in her armpit as if to articulate hair and she has pubic hair next to her sharp hip bones. She is in no way idealized, instead Klimt is embracing the natural female body and going against the perfectly hairless Venus’s of the artists before him.

On the second page of this website, you will find two of Klimt’s later works. The Virgin (1913) and The Bride (Unfinished) (1917-1918). The J. Paul Getty Museum says about The Virgin: “The painting is a summation of Klimt’s overarching theme of female erotic dream states, in which he explores its various manifestations over life, from virginity to mature sexuality.” If Klimt was indeed trying to paint seven women as a manifestation of maturing sexuality, why has he painted them all in a state of either sleeping or waking, and curled up into each other? The women are nude and supposedly in a bed together, but does that make it sexual? What this says is that Klimt has taken a situation, that may not appear to the 21st century eye as a sexual situation, and has turned it either into some kind of homosexual orgy, or each woman has taken the role of a period of sexual maturity throughout life. If the latter is the case, none of these women look alike and they all seem to be the same age or at least in the same age group. There is also a confusing fact that the title is “The Virgin” speaking singularly about one specific person. Are we to suppose that the central figure is then this “Virgin” and that the women around her are manifestations of sexual maturity? If one were to look at this painting, now, in 2018, it would be very doubtful that they would see anything other than a few women, who appear to be nude, taking a nap. In context with the time period it was probably very scandalous, as most of Klimt’s art was, but it probably did carry sexual connotations, especially with its title. Once again, we have a painting of nude woman sexualized by Klimt, purely by the title in this case. This painting is the prime example of Klimt using the female form as ornament. The only objects in the paintings are the women and the patterns on the material around them.

Then, we have The Bride (Unfinished), which is eerily similar to that of The Virgin. There are several women to the left of the canvas piled on each other and in blankets, but unlike The Virgin, these women are obviously nude. Each one showcases a different body part, a back and a rear end, breasts, arms framing a blushing face. On the right side is the unfinished figure, of whom we might assume is this bride. She is bare breasted and covered on her lower half with a translucent cloth, underneath which we can see her genitals, obscured by pubic hair. Underneath her unfinished arm is an eye, the rest of the figure is covered in blankets.

This painting has taken The Virgin and said to the viewer “Yes, this is sexual.” Not only are the figures here exposed and obviously nude, but the main figure on the right is laying with her legs open, fully exposing herself to the viewer.

Not just in art history, but every history of every civilization, there are tales of injustices. There are reputations that are not deserved, there are rumors and stereotypes and lies that are repeated so often and spread so far, it is hard to know what is the truth. Gustav Klimt, the great Austrian painter in gold, has been labeled as a feminist. As a sexual liberator of women. A man who paints for the male gaze, who takes stories of strong women and removes their clothes, and removes their narratives. Choses to paint them in a moment that erases their strength. A man who walks around his studio, barely wearing clothes, and draws women masturbating to keep the drawings for himself. A man who exaggerated a starving woman because it was pleasing to him. A man who took Judith and removed her from the slaying of Holofernes, the sacrifice she made for her people, and instead painted her as an erotic nude woman covered in ornament and gold. A man who painted Danae, but painted her erotically as she was being raped by Zeus. A man who drew women he knew and employed for his own sexual pleasure. Gustav Klimt was not a feminist. The only question left is: if it was a sexual liberation of women for his own pleasure, is it still sexual liberation?

All images from The Met Collection and WikiArt.